The Government of India has promoted Digital Payments over multiple initiatives in the past few years, one of which was an announcement in the Finance Minister’s Budget Speech 2019, removing the Merchant Discount Rate (“MDR”) charges applicable on payments made through the following electronic modes:

- Debit Card powered by RuPay;

- United Payments Interface (BHIM-UPI); and

- Unified Payments Interface Quick Response Code (UPI QR Code).

The Government’s rationale for the move was that MDR and other fees involved in digital payments increased costs for merchants, which disincentivized them from offering digital payment modes to their customers.

The removal of MDR charges was implemented by way of amendments to the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 and the Finance Act, 2019. These legislative changes are summarized below:

- Section 269SU of the Finance Act provides that, “Every person, carrying on business, shall provide facility for accepting payment through prescribed electronic modes, in addition to the facility for other electronic modes, of payment, if any, being provided by such person, if his total sales, turnover or gross receipts, as the case may be, in business exceeds fifty crore rupees during the immediately preceding previous year.”

- Further, under Section 271DB of the Finance Act, any shops, business firms or companies with an annual turnover of over INR 50 crores who do not provide digital payment facilities to its customers as prescribed by Section 269SU, will be liable to pay a penalty of INR 5,000/- per day for such failure.

- Finally, Section 10A of the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 which was inserted by the Finance Act provides that no bank or system provider shall impose and charge on a payer, or a beneficiary receiving payment, through the electronic modes prescribed under Section 269SU of the Act. The ‘prescribed electronic modes’ of payment for the purpose of Section 269SU are UPI and RuPay Debit Cards, as provided above. This was specified by Rule 119AA to the Income Tax Rules, 1962, which came into effect on January 01, 2020.

MDR – What does it mean to FinTechs and the Digital Payments ecosystem?

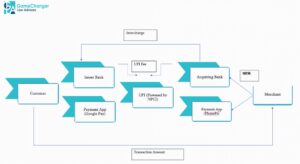

Digital payments in any B2C (business-to-consumer) transaction involve a number of counterparties. These include the paying customer, the merchant, the customer’s bank (“Issuing Bank”), the merchant’s bank (“Acquirer Bank”), and the Payment Service Provider (“PSP”, which term includes FinTech startups in the payment space such as PhonePe, Google Pay and BHIM). Each of these intermediate parties takes on additional costs and credit risks to enable such payments, which are offset to an extent by certain fees that they receive pursuant to such digital payments.

To illustrate (see diagram below):

- In a UPI transaction, banks and PSPs pay the National Payments Corporation of India (“NPCI”) a “UPI usage charge”, as consideration for their usage of the UPI network and utilizing NPCI as the settlement agency for such transactions.

- To ensure acceptance of its payment mode, the Acquirer Bank pays the Issuing Bank a fee known as an “interchange fee”.

- The MDR, or Merchant Discount Rate, is a fee paid by the merchant to its bank for accepting payments via UPI, or any other payment mode. This is typically calculated as a percentage of the transaction value undertaken through UPI.

Author’s Take

Continued MDR for SMEs: In 2018, the RBI had hiked the MDR rate, and defended the move, citing that point-of-sale infrastructure providers (i.e. banks) would recover costs only through MDR. However, this was met with heavy resistance by small and medium sized merchants, who claimed that MDR of 0.25% to 1% would significantly affect their margins, and expected relief from the Finance Ministry. However, the Government’s Zero-MDR decision is aimed solely at entities with an annual turnover in excess of INR 50 Crores, and hence is unlikely to offer respite to small enterprises, or increase adoption of UPI and RuPay among them, as desired.

Reduction of income for Banks and PSPs: The move takes away any income that banks and PSPs such as UPI apps may receive to enable digital transactions. This may disincentivize banks and PSPs from promoting UPI and RuPay, arguably the objective of this policy move. This may also lead them to shift their business model to selling financial data of their users. In an ecosystem where privacy rights of individuals are gaining greater currency, it is crucial that regulatory changes do not nudge industry players into undermining these rights.

Subsidizing digital payments infrastructure: Further, while these fees may increase transaction costs on the face of it, they serve to subsidize other costs involved in the building, maintenance and delivery of digital finance infrastructure. Some of these costs include software developer compensation, customer service charges, setting up of merchant distribution networks through point-of-sale machines, operation of data centres and others. While merchants of a certain size cannot refuse to accept payments through UPI and RuPay debit cards, it remains to be seen whether banks, in the face of increased costs, will find ways to disincentivize their use and acceptance.

Conclusion: The 2016 Watal Committee Report, and the 2019 Nilekani Committee Report on digital payments both acknowledge that MDR is essential to the sustained growth of the industry. While the Watal Committee Report believes that the fee should be market-fixed, the Nilekani Committee Report suggests that a standing committee of the RBI review the rate periodically, such as in the case of benchmark rates. It is crucial for the upcoming Budget announcement to clarify the manner in which Zero MDR is to be operationalized. It must clear the air on whether the government will now bear the costs of digital payments infrastructure, through a subsidy for banks and PSPs. Players in the payment space would benefit if the announcement included a sunset period until which the Zero MGR regime would prevail, after which they could revert to a market-led model of deciding incentives, or to the model proposed by the Nilekani Committee Report. It is only then that the policy’s objectives of larger digital inclusion will be met.